Rising Interest Rates

The speed and magnitude of economic developments in recent years have been nothing short of remarkable. The last four years have felt like one endless sequence of unprecedented events in rapid succession.

2023 has been almost as extraordinary as the previous three years. Much like the spectacular spike in inflation, the pace of disinflation in 2023 has been remarkably rapid as well. Headline CPI inflation has fallen from above 9% to around 3% in the last five quarters. Core PCE inflation is now below 4% year-over-year and has grown at an annualized pace of just about 2% in the last three months.

The U.S. economy has also been remarkably resilient in the third quarter of 2023. As a result, the odds of a recession have receded steadily in the minds of investors. On one hand, this combination of lower-than-expected inflation and higher-than-expected growth should have given investors reason to celebrate. After all, it could have been viewed as a successful milestone in the journey to a soft landing.

However, these hopes are now at risk from perhaps the most remarkable outcome of the third quarter – a sharp rise in long-term interest rates. A swift increase of more than 1% in the 10-year Treasury bond yield was the primary driver of the stock and bond market selloff in September.

The recent market turbulence has ignited renewed fears about the future trajectories for growth and inflation. The potential outcomes range from stagflation in the near term to a deeper eventual recession from the adverse impact of higher interest rates.

We focus our analysis here on answering two key questions.

- Why have long-term rates risen so sharply?

- And what are the likely implications of such an increase?

Drivers of Higher Rates

Just as it appeared that we may be reaching the end of this tightening cycle, the Fed emphatically signaled a “higher for longer” stance at its September meeting. The hawkish Fed announcement on the monetary front coincided with a political disagreement on the level of government spending and fueled another upward spiral in long-term interest rates.

In its simplest fundamental framework, changes in long-term interest rates are influenced by three factors.

- Changes in inflation expectations

- Changes in growth expectations

- Changes in the “term risk premium” or compensation for bearing interest rate risk

We take a closer look at each of these factors. Along the way, we also identify some peripheral influences that may be exerting upward pressure on long rates.

Probably Not Driven by Inflation

We have made significant progress with disinflation in recent months … probably more than many had expected. And yet the concern remains that inflation is still above 2% and any unusual economic strength will simply stoke it further, send rates higher and trigger an even deeper recession down the line.

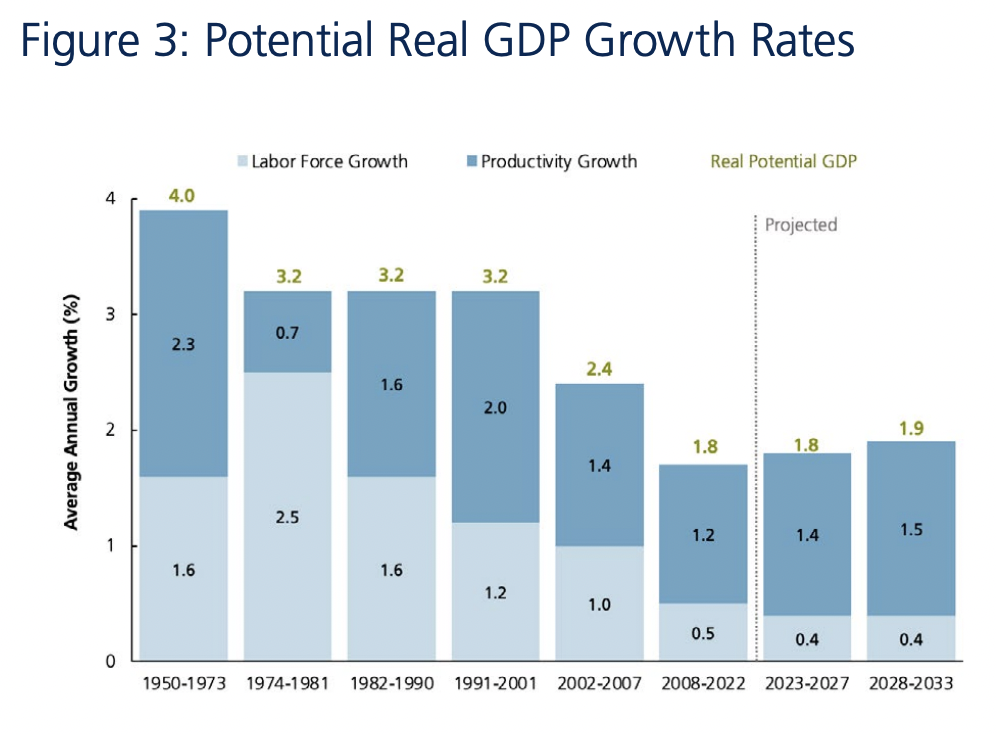

We believe that inflation is firmly on its way down and remain optimistic that the recent trend of disinflation will continue. We summarize our inflation outlook in Figure 1 below.

Source: Factset

Source: Factset

The dark blue line in Figure 1 shows headline CPI inflation. It peaked at 9.1% in June 2022 and has since declined to 3.7% in August. By now, it looks like we are well past the peak in inflation.

The small spike in headline inflation at the far right is attributable to the recent rise in oil prices. Barring a major escalation of geopolitical risks, we believe there is limited upside to oil prices after these gains. Besides, energy costs are notoriously volatile and core inflation, which excludes food and energy, remains in steady decline.

The decline in core inflation is particularly encouraging because it is known to be sticky. Wages are a key component of core inflation. The green line in Figure 1 shows growth in average hourly earnings as a proxy for wage inflation.

Wage inflation peaked almost a year and a half ago at around 6%. It has since fallen steadily to just above 4%. It is interesting that we have achieved this disinflation without any major disruption in the labor market.

The light blue bars in Figure 1 show that the unemployment rate was steady between 3.4% and 3.8% as wage inflation declined from 6% to 4%. This leads us to believe that we have not yet seen meaningful demand destruction. Instead, we suspect that the pandemic created transitory supply side shocks which have since abated to provide meaningful disinflationary relief.

We conclude from Figure 1 that recent disinflationary trends remain intact and will likely persist as the economy cools further in response to higher interest rates.

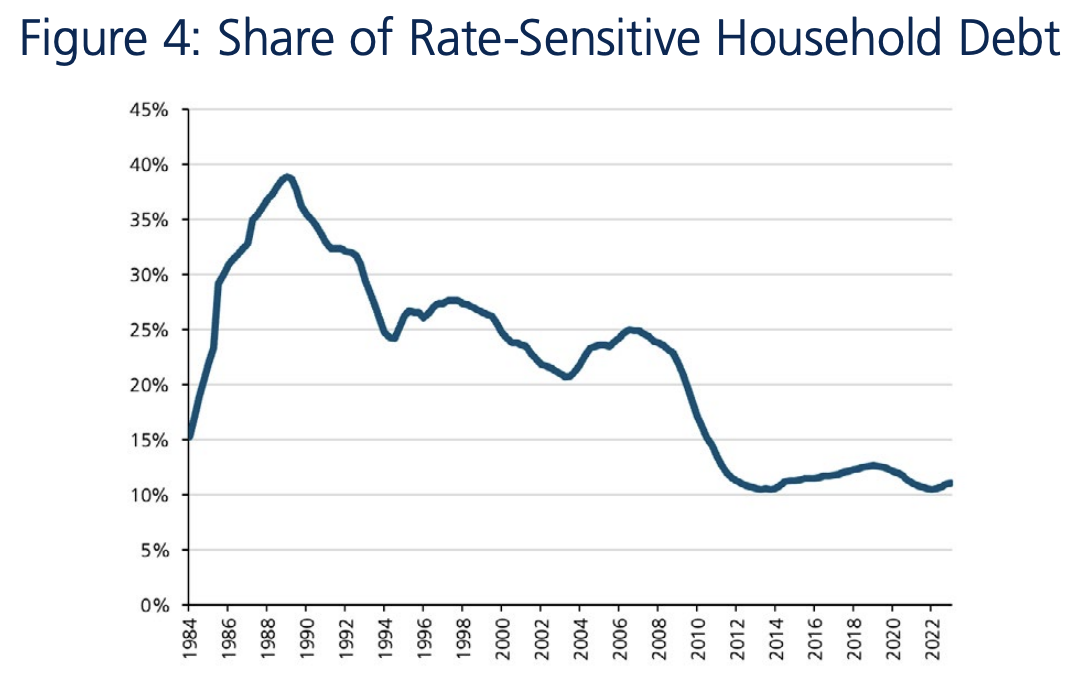

We have further evidence to support our conclusion that inflation is not the primary driver of higher long-term interest rates. Figure 2 shows 10-year Treasury yields and 10-year breakeven inflation expectations priced into inflation-protected bonds.

Source: Factset

Source: Factset

The dark blue line in Figure 2 shows the dramatic increase in 10-year Treasury yields in recent weeks. The 10-year breakeven inflation rate in light blue has remained virtually unchanged over that period. Investors are clearly not pushing long-term interest rates higher because of higher inflation expectations over the next 10 years.

Likely Not Triggered by Growth Either

Since inflation expectations have remained practically unchanged, the rise in nominal interest rates has essentially led to an increase in real (nominal minus inflation) interest rates.

A typical driver of changes in real interest rates tends to be a change in growth expectations. At first glance, it is tempting to attribute higher long-term interest rates to higher long-term growth expectations. After all, we did allude earlier to unexpected recent resilience in economic activity.

But we rule out this possibility on further reflection. Yes, the odds of a recession in the near term may have receded. But it is unlikely that a burst of economic strength in the short run could materially increase long-term growth rates over the next 10, 20 and 30 years.

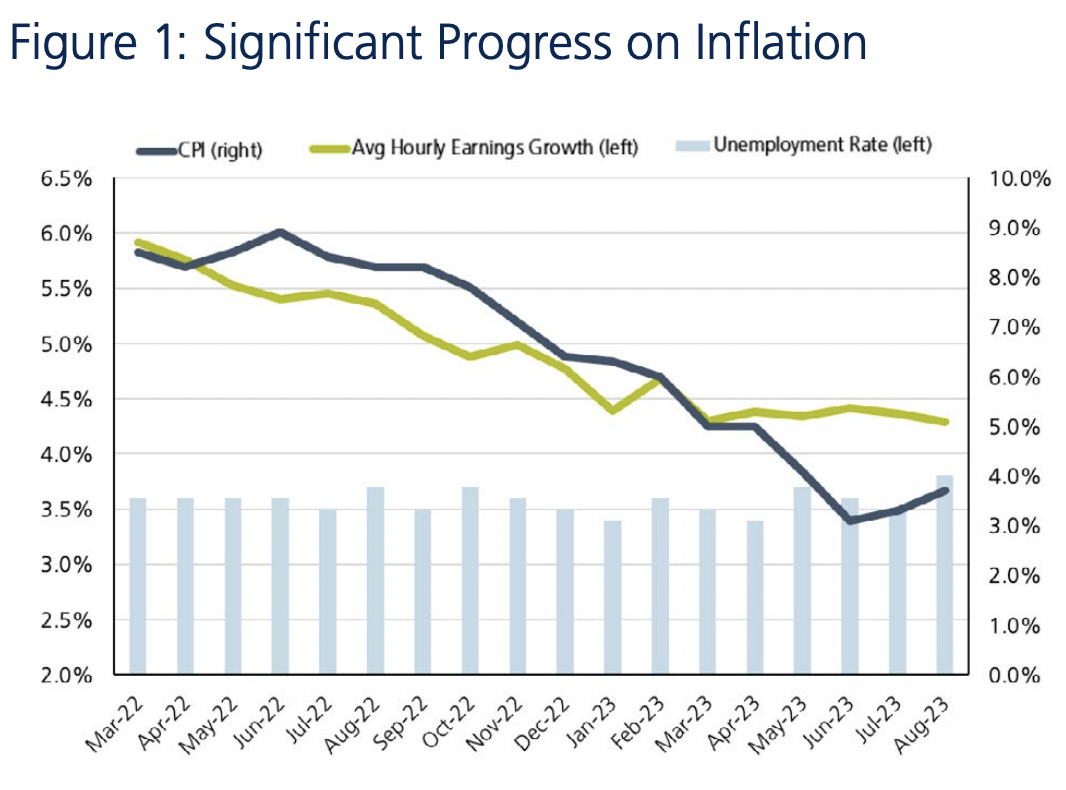

In fact, we know that the two drivers of long-term real GDP growth are labor force growth and productivity growth. We show how these building blocks have historically contributed to the potential growth rate of the U.S. economy in Figure 3.

Source: Congressional Budget Office 1950-2022, Whittier Projections 2023-2033

We can think of the potential growth rate of an economy as the natural speed limit at which it can operate without unleashing inflation.

We see in Figure 3 that the potential GDP growth rate of the U.S. economy has slowed steadily over the last 70 years. Productivity gains held steady for most of that period before falling in the Global Financial Crisis and the Covid pandemic.

However, an aging population has dramatically altered the growth dynamics of the U.S. economy. As the baby boomers age, the labor force participation rate has declined steadily in recent years. Labor force growth has slowed down from around 2% in the first 40 years of this period to barely 0.5% in the last 15 years.

We project that this trend will continue well into the future. Demographic shifts are slow to unfold and predictable in their evolution.

We see nothing to suggest that the long-term potential GDP growth rate of the U.S. economy has risen in recent months. It is unlikely that changes in growth expectations can explain the rise in long-term interest rates.

We recognize that a dramatic shift in immigration policy or a significant increase in AI-induced productivity growth could change this dynamic. But we see these as more speculative possibilities at the moment.

Conceivably Related to Policy Risk

We finally assess if investors are pricing in a greater level of risk and uncertainty in their outlook for bonds. In that scenario, investors would demand greater compensation for bearing the risk of investing in long-term bonds in the form of lower prices and higher yields.

Let’s look separately at the risk of misguided central bank monetary policies and imprudent fiscal spending policies from the central government.

We know the Fed has signaled a higher-for-longer stance on short-term interest rates. The big risk with this approach is that monetary policy may become too restrictive at some point and throw the economy into a recession. However, such an outcome would lead to declining, not rising, long-term interest rates.

While monetary policy risk doesn’t inform our current inquiry into rising long rates, we will come back to it in the next section on the implications of higher short-term and long-term interest rates.

After ruling out inflation, growth and monetary policy risks as drivers of higher long-term rates, we may finally have a plausible candidate in the form of higher fiscal policy risk.

Federal debt has risen sharply as a result of the fiscal stimulus provided during the pandemic; it now stands at $33 trillion and 120% of GDP. While the magnitude of this debt burden has been known for some time now and is hardly new information, investors may finally be getting concerned about the lack of both fiscal discipline and bipartisan alignment in Washington.

The Congressional Budget Office now projects the public debt to GDP ratio to reach 200% in the next 30 years. And the political dysfunction in recent months has ranged from a protracted battle on the debt ceiling to a near-shutdown of the government and a subsequent change in House leadership from a revolt by Republican hardliners. In the meantime, interest rate volatility has picked up and bonds are now poised to generate negative total returns for an unprecedented third consecutive year.

It is quite possible that investors are repricing long-term bonds to higher yields in response to greater fiscal policy risk and higher asset class risk.

We also suspect that a couple of other factors may be accentuating the sharp rise in bond yields. After the debt ceiling crisis in May, Treasury issuance has been higher while Japan and China have reduced their purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds.

The imbalance arising from more supply and less demand may be creating a liquidity-driven price dislocation in the near term. And we would not rule out a speculative momentum-driven trend that continues to push prices lower and yields higher.

We summarize this section by attributing the recent rise in interest rates to a repricing of fiscal policy and asset class risks. In the process, we observe that neither long-term inflation expectations nor growth expectations have changed materially.

We also believe that short-term liquidity effects and speculation may have pushed interest rates beyond fair values based on the fundamental repricing of risks. We believe that the 10-year and 30-year Treasury bond yields are likely to normalize closer to 4% than above 5% in the coming months.

We next look at the likely impact of rising rates on the economy and markets.

Implications of Higher Rates

Rapid monetary tightening has led to financial accidents in the past. We almost got one in March in the form of a banking crisis. However, prompt and powerful policy actions contained the damage to the collapse of just a handful of regional banks.

The prospect of higher rates for longer is now raising concerns about what might break next. As these worries mount, investors are starting to bring the hard landing scenario back to the fore again.

Higher Recession Odds?

The ability of the U.S. economy to first withstand high inflation and now higher interest rates has caught many by surprise. Based on history, many conventional indicators have already been predicting the onset of a recession by now.

The more notable ones include an inverted yield curve for over a year, a continuous decline in the Leading Economic Indicators index for almost a year and a half and a collapse in year-over-year money supply growth to levels last seen in the Great Depression.

Instead, the job market and the consumer have remained resilient. Does the solid job market run the risk of creating an economy that is still too hot and, therefore, poised to unleash inflation at any moment? We don’t believe so.

Job growth has now declined steadily for several months from its torrid stimulus-induced pace. And the consumer and the economy will continue to face future headwinds from the eventual lagged effects of higher interest rates, the depletion of excess savings from the Covid stimulus and the resumption of student loan repayments.

We also show how higher interest rates may affect consumer spending differently than they have in the past.

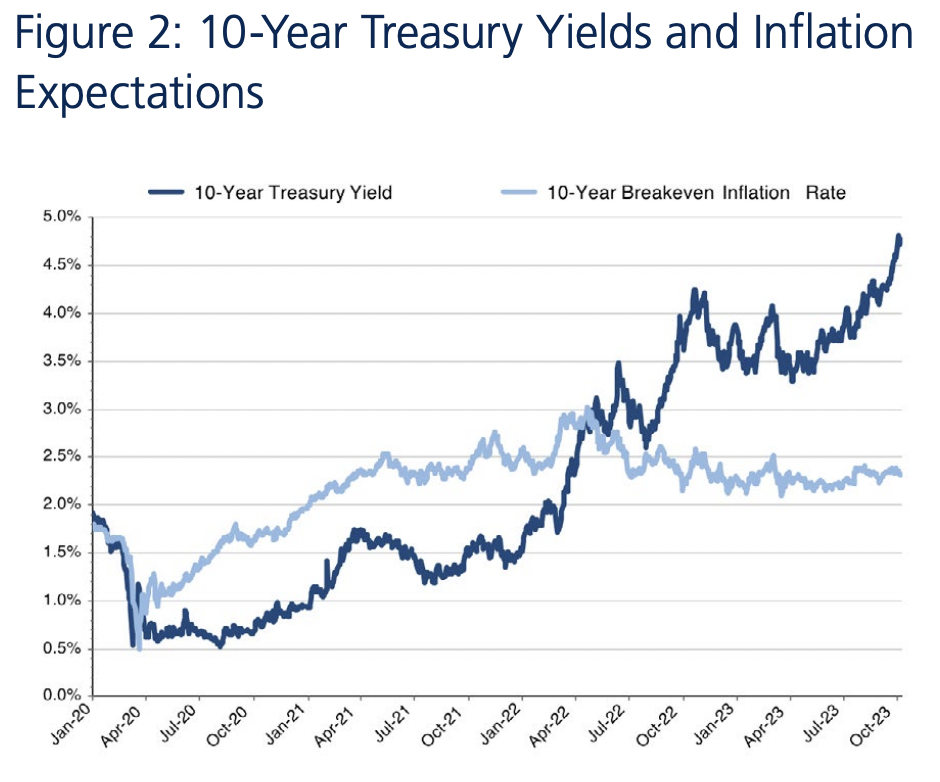

Mortgages and auto loans are two of the bigger components of household debt. Consumers locked in low rates on those debt obligations during the long periods of easy money between 2008 and 2021. We see that clearly in Figure 4.![]()

Source: WSJ, Moody’s Analytics

Only 11% of outstanding household debt in 2023 carries rates that fluctuate with benchmark interest rates. By contrast, this proportion was above 35% in the late 1980s.

Although floating rates on credit card loans are rising with the Fed’s tightening, a significant portion of consumer debt is fixed at low rates from a few years ago. This has allowed many households to continue spending despite the rise in interest rates.

Also, households are still paying less than 10% of their disposable income to stay current on their debts even with higher rates. This is well below the high from 2008 and is also lower than the post-crisis average.

We believe the prevalence of fixed-rate debt on consumer balance sheets has made the U.S. economy less rate-sensitive.

Here are a few observations which highlight a similar effect on corporate balance sheets and income statements.

- Corporations also refinanced a lot of their debt to longer maturities at lower fixed rates. Almost half of S&P 500 debt is set to mature after 2030.

- The notional share of investment grade and high yield debt maturing within two years is around 15%, well below its 25% share in 2008.

- Despite the sharp increase in Fed funds rates, net interest payments for companies in 2023 are actually lower than they were a year ago.

We acknowledge that the lagged effects of higher rates will continue to slow growth. We do not, however, expect a significant recession in 2024.

Policy and Portfolio Considerations

The Fed funds rate is currently at 5.4%. The latest Fed projections point to one more rate hike in 2023 and two rate cuts in 2024. With policy rates projected to remain above 5% for over a year, we understand investor concerns about a potential Fed misstep.

As inflation falls below 4%, short-term interest rates are becoming restrictive by historical standards. Any continued decline in inflation will make current monetary policy even more restrictive. The resulting increase in real rates could trigger a recession.

While we recognize this risk, we feel that a sufficiently responsive Fed will manage to avoid it. To the extent that the next recession will be induced by Fed policy, we believe the Fed will also have the ability to manage it before it becomes entrenched.

We believe that the growing evidence of a slowing economy and declining inflation gives the Fed more flexibility than what can be inferred from their forecasts. We discuss potential Fed actions across different economic outcomes.

Let’s assume that growth begins to slow materially to risk a recession. In this setting, inflation is also likely to come down. Now the Fed no longer needs to be restrictive because the inflation war has been won; it can begin to cut rates. However, if inflation doesn’t subside to desired levels, it may well be on the heels of a stronger economy in which case a recession becomes moot.

We do not expect to see either of the two scenarios that invalidates our outlook – high inflation in the midst of a recession or a stubborn Fed which keeps rates high going into a recession.

At a portfolio level, we remain constructive on both the stock and bond markets. Long-term bond yields have already risen significantly. The 10-year bond yield reached a high of 4.88% in the first week of October; we believe it may have more room to fall from this level than to rise further. Bonds have clearly repriced to offer more compensation to investors.

The rise in interest rates has also taken a toll on stocks. By the first week of October, stocks had fallen by almost -8% from their July highs. On one hand, the rise in interest rates reduces stock valuations. On the other hand, lower odds of a recession improve cash flows. At current valuations, we believe stocks still offer above-average returns relative to bonds over the next year.

Summary

We set out to understand the drivers and implications of the recent rise in long-term interest rates. Here is a summary of our key observations.

- We rule out higher inflation, growth and monetary risk as the drivers behind the recent rise in long-term interest rates.

- Instead, we attribute the recent rate increases to a higher risk premium (i.e. risk compensation), reduced liquidity and greater speculation.

- Monetary policy is getting restrictive and, even without any more rate hikes, will become more so if we see less inflation.

- Policymakers will eventually avoid the risk of major financial accidents from remaining overly restrictive.

- Both stocks and bonds are attractive after repricing lower in recent weeks.

We recognize that the coast is far from clear and a lot of uncertainty still persists. We respect the need for greater vigilance in portfolio management during these turbulent times. We continue to exercise caution and care in client portfolios.

The recent rise in long-term interest rates has renewed fears about the future trajectories for growth and inflation.

Long-term bonds are likely pricing in greater fiscal policy risk and higher asset class risk.

Both stocks and bonds are attractive after repricing lower in recent weeks.

From Investments to Family Office to Trustee Services and more, we are your single-source solution.

Source: Factset

Source: Factset Source: Factset

Source: Factset